Our History

History Of The RDR

Extending from an intake on the Rangitata River at Klondyke, to a discharge at Highbank on the Rakaia River, the 67 kilometre RDR canal is recognised as one of the most visionary engineering accomplishments of its time.

Over eighty years on, we reflect on how this government-lead initiative has helped shape our region.

A Timeline of Significant Events

A topographic survey was started in Mid Canterbury. Council, local bodies and government department representatives met to discuss irrigation of the plains..

Surveying for the Mid Canterbury irrigation schemes commenced. The present irrigation scheme was planned, started and spearheaded by irrigation engineer Mr T.G. Beck.

Construction on the Ashburton Lyndhurst scheme began.

Decision to build the Rangitata Diversion Race for irrigation and power generation.

Construction began on April 2 and continued until 1945. With the influx of labour, Public Works camps were established to accommodate single men and families.

Work was well underway when World War II broke out and interrupted construction for a time.

Syphon built under the Hinds River.

Slips at Surrey Hills threaten the project but eventually, construction of syphons starts.

September 28, Highbank Power Station approved.

Two-thirds of race excavation work completed.

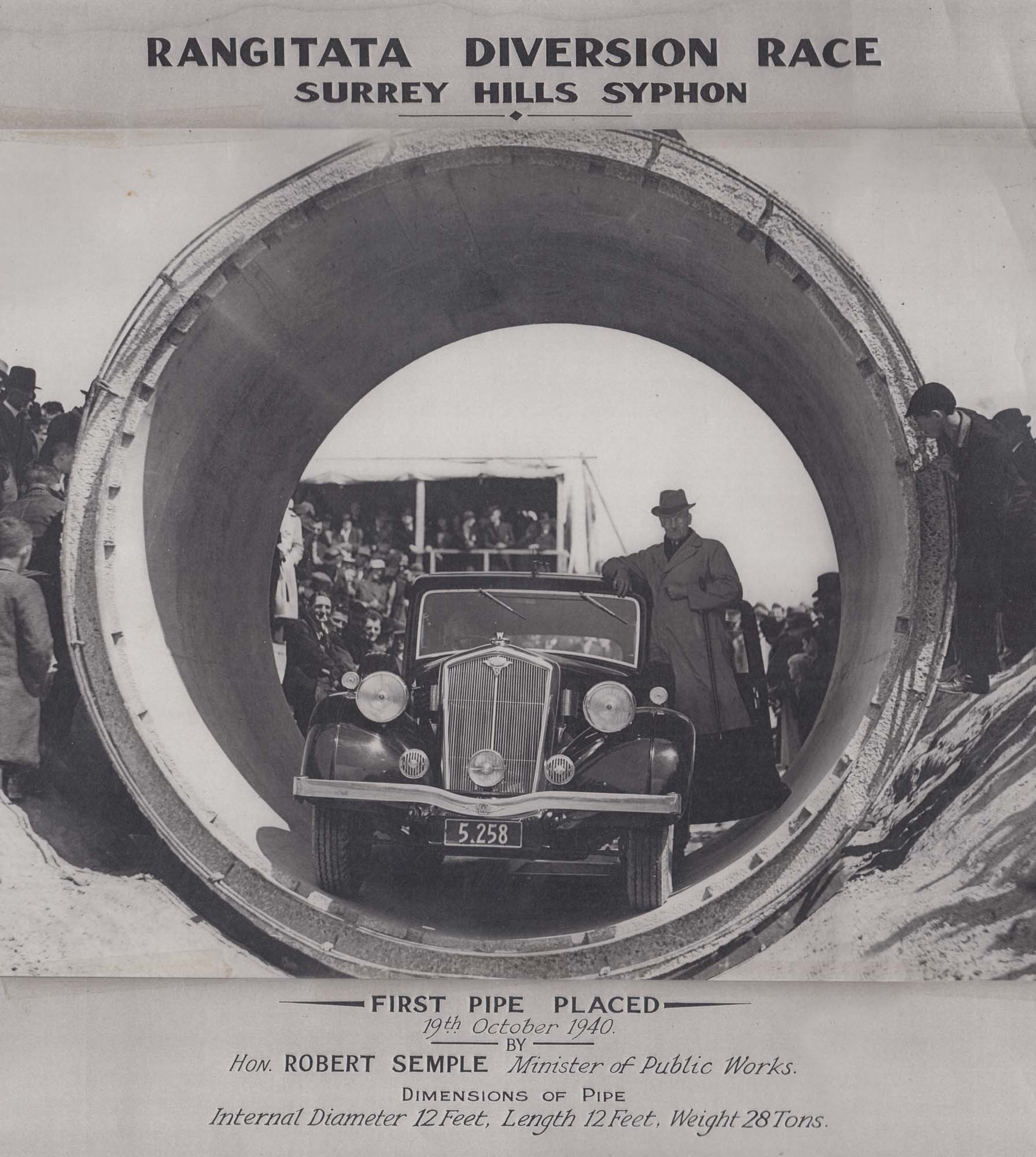

October 10, Works Minister Bob Semple lays first pipe of the Surrey Hills syphon.

May, South Ashburton syphon dug out.

Race completed – A Department of Agriculture report said carrying capacity of the land had been increased from one to six sheep per acre.

June 8, Highbank Power Station generates power.

Installation of intake sandtrap begins.

August, decision to build Montalto Power Station.

January, construction on Montalto Power Station begins.

June, Montalto Power Station generates power.

On 1 October, the government transfers the ownership of the RDR to a user owned limited liability company called Rangitata Diversion Race Management Ltd (RDRML).

From 1998 to 2008 Resource Consents and Rangitata River Water Conservation Order processed.

Trustpower purchases Montalto and Highbank Power Stations.

Bioacoustic Fish Fence (BAFF) installed.

Fish Screen constructed at South Ashburton/Hakatere intake.

Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) control system installation.

Barrhill Chertsey Irrigation Scheme (BCI) started.

Mayfield Hinds Scheme Carew storage ponds built.

Valetta scheme piped.

Highbank pump station commissioned (pumping water from the Rakaia River into the RDR, primarily for BCI).

Mayfield Hinds and Valetta irrigation companies merged to form MHV Water.

Ashburton Lyndhurst Scheme piped.

Construction of replacement fish screen commenced (March)

1 in 200 year floods in Mid Canterbury cause damage to RDR

Replacement fish screen commissioned (May)

Historic Overview

It is difficult to imagine how Mid Canterbury, or the ‘trans-Rakaia Desert’ as it was originally referred to, looked over 160 years ago. The fact that Ashburton was one of the last districts of Canterbury to be settled is testament to the stoic pioneering spirit of those hardy souls who took up the challenge of turning what was deemed ‘isolated wasteland’ into the thriving district it is today.

Most of the county’s runs had been spoken for by the mid-1800s and the township of Ashburton was pegged out in 1864. When the Ashburton County Council was formed in 1876 water race planning was an immediate focus, channelling much needed water around the county for household and livestock use.

Preliminary work on a ‘Proposed Scheme for Irrigating the Plains of the Ashburton County’, was carried out in 1884 by then county engineer William Baxter, however it was almost 50 years before construction began on an overall scheme which was remarkably similar to Baxter’s original plans.

The present irrigation scheme was planned, started and spearheaded by irrigation engineer Mr T.G. Beck, under the direction of Mr J. Wood, Engineer-in-Chief of the Public Works Department (PWD). Beck’s contribution is recognised on the Engineering New Zealand website (formerly Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand – IPENZ).

The catalyst for the construction of RDR (“The Race”) was The Great Depression in the 1930s, a period when food rationing was commonplace and farming was very tough post World War One. As export earnings plummeted farmers stopped spending, with drastic effects. Jobs and wages were slashed across the whole country leaving thousands of men unemployed and forced to become swaggers (roamed the countryside looking for work) in order to provide for their families.

In November 1935 the New Zealand Labour Party came into power amid promises to introduce large Public Works schemes. As Minister of the Public Works Department, Hon. R (Bob) Semple is considered to have been a driving force behind Government investment in the RDR.

Having been unemployed himself and forced to walk the country looking for work, Semple had a unique perspective on what needed to happen at this time. In a Government booklet ‘Water Put to Work’ (insert website link?), Semple claimed; “We as a nation cannot afford the continued idleness of such extensive resources not only for our own good, but for the benefit of the world at large”.

Construction of the RDR

Employment, Hydroelectricity and Irrigation

Built between 1937 and 1944, the RDR was a Labour Government led Public Works scheme which was introduced to address three significant challenges: create jobs for the unemployed; generate hydroelectricity and increase productivity on the parched plains of Mid Canterbury.

Offering meaningful employment was important for morale as well as the national economy. Over time, roles were created for over 400 people, including: engineers, surveyors, overseers, foremen, machinery operators, drivers, concrete workers, carpenters, steel benders, blacksmiths, plumbers, mechanics, electricians, firemen, office staff and labourers.

Men, including a sizeable contingent from the local runanga, Arowhenua, who were offered the chance of full-time work on the RDR and associated irrigation schemes grabbed the opportunity. Many had been on unemployment schemes where food parcels, such as flaps of mutton in sugar bags, were handed out to needy families. Single men and families moved into primitive camps during the 1930s and 1940s, grateful for the regular income.

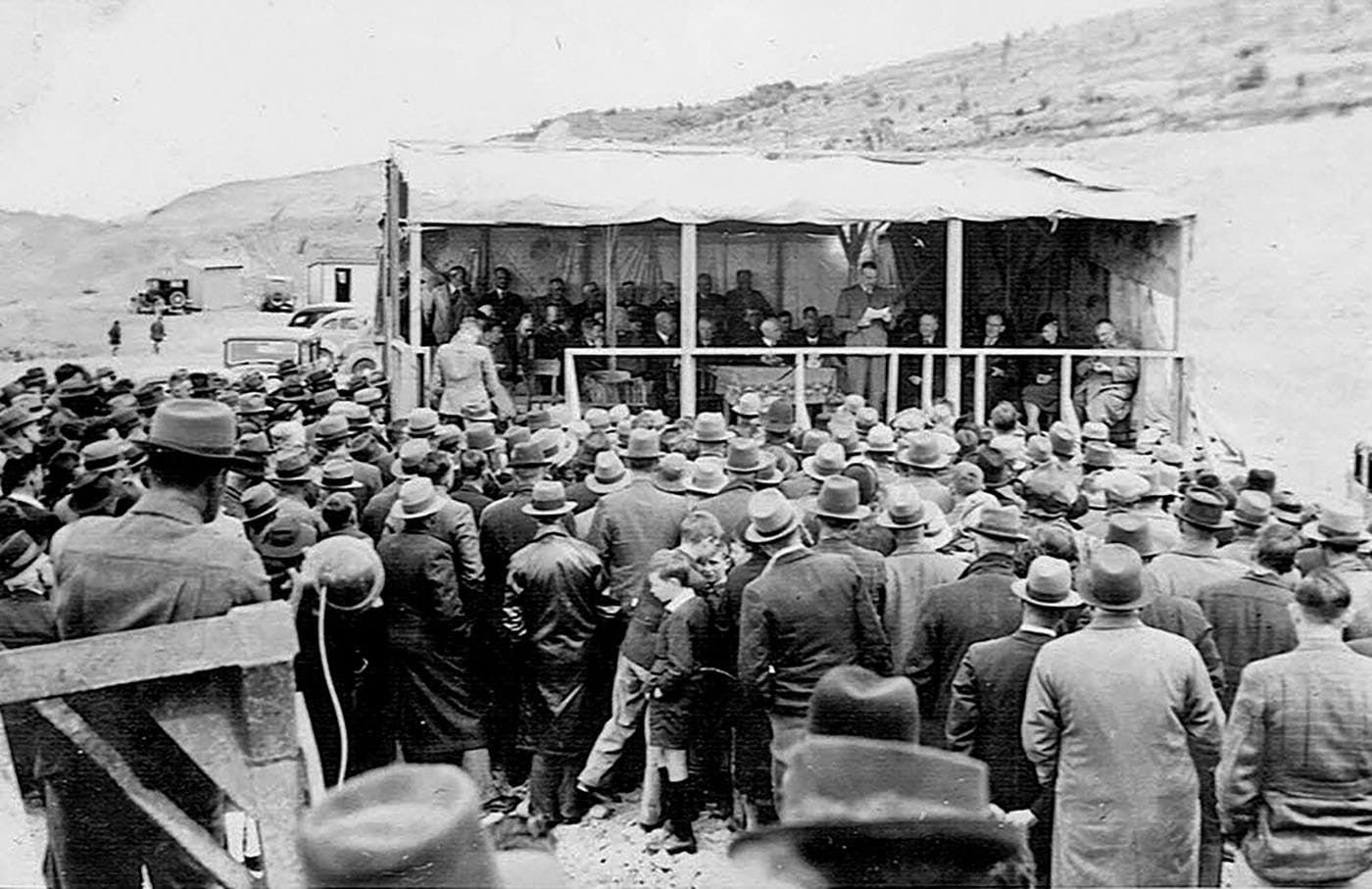

Hon. R. Semple was Minister of Works when the Labour led Public Works Department approved plans for local investment in the RDR. Described as a charismatic leader, Mr Semple is pictured surrounded by dignitaries as he addressed an eager crowd of onlookers, many of whom were farmers, at an event marking the first concrete pipe laid for the RDR Surrey Hills syphon on 19 October 1940. (Image: Ben Lewis archives).

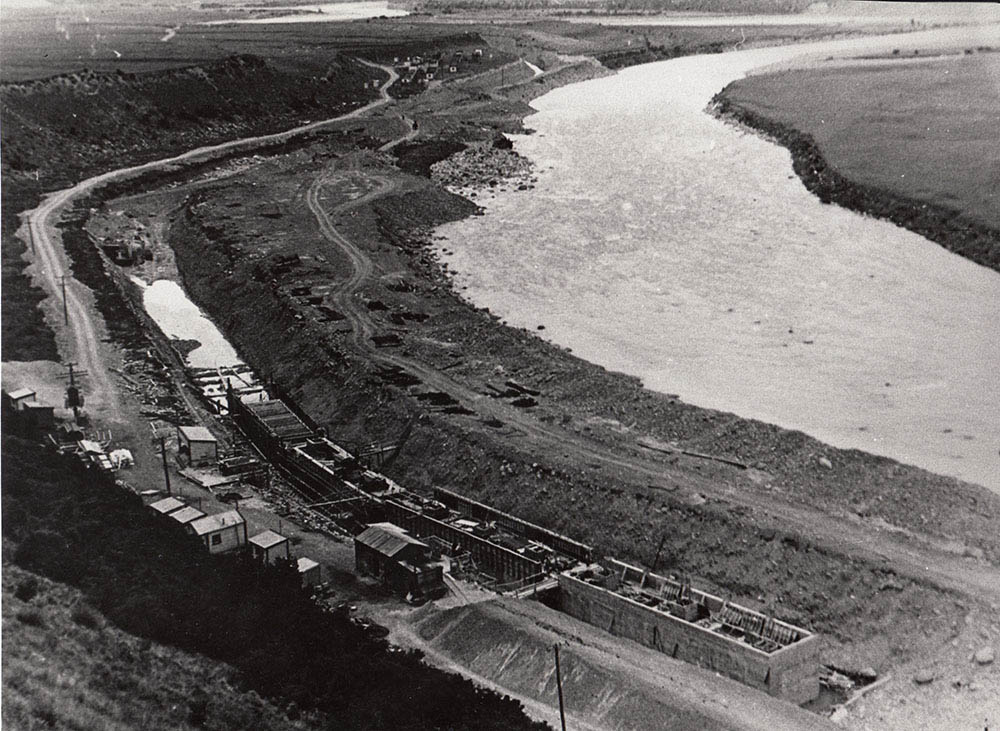

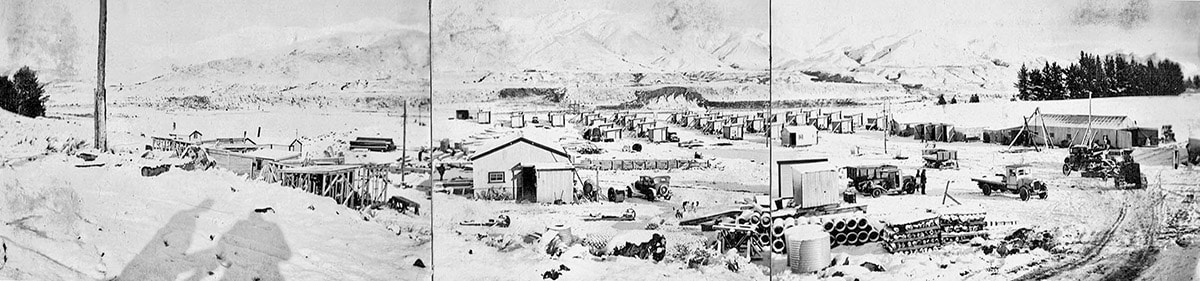

Public Works camps sprung up throughout the region and menfolk were grateful for the opportunity to finally have meaningful work. Conditions were rudimentary, as was the case for many homes during this era, and a welcome degree of camaraderie soon set in. (Image: Ben Lewis archives).

The Heaviest Mile

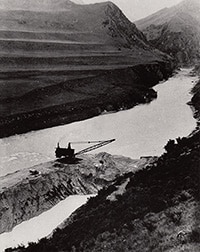

Picks, shovels and wooden wheelbarrows were the tools of the day on 2 April 1937 when work started on the massive project. The first section was dug at Klondyke in the Rangitata Gorge, about one mile down from the race intake. As the trench deepened to the required 12 foot (3.65m) depth, workmen had to shovel in stages.

Timber landings were built on three levels at the sides of the trench, men dug out the debris and threw it up to a worker at the next highest level, who, in turn passed it up to the man at the top.

In all, over five million cubic yards of material, soil, silt and boulders were excavated during the construction of “The Race” as locals fondly dubbed the diversion race. An average of 280,000 cubic yards (218,000 m3) were excavated each month at a cost of one shilling per cubic yard (approx $5/m3 in 2018).

Klondyke was called “the heaviest mile,” where 450,000 cubic yards (344,000 m3) had to be shifted by dragline and bulldozer. The first machinery to arrive was a steam dragline, PWD 943 speeder face shovel, RD7 Caterpillar bulldozers and Athey Wagons.

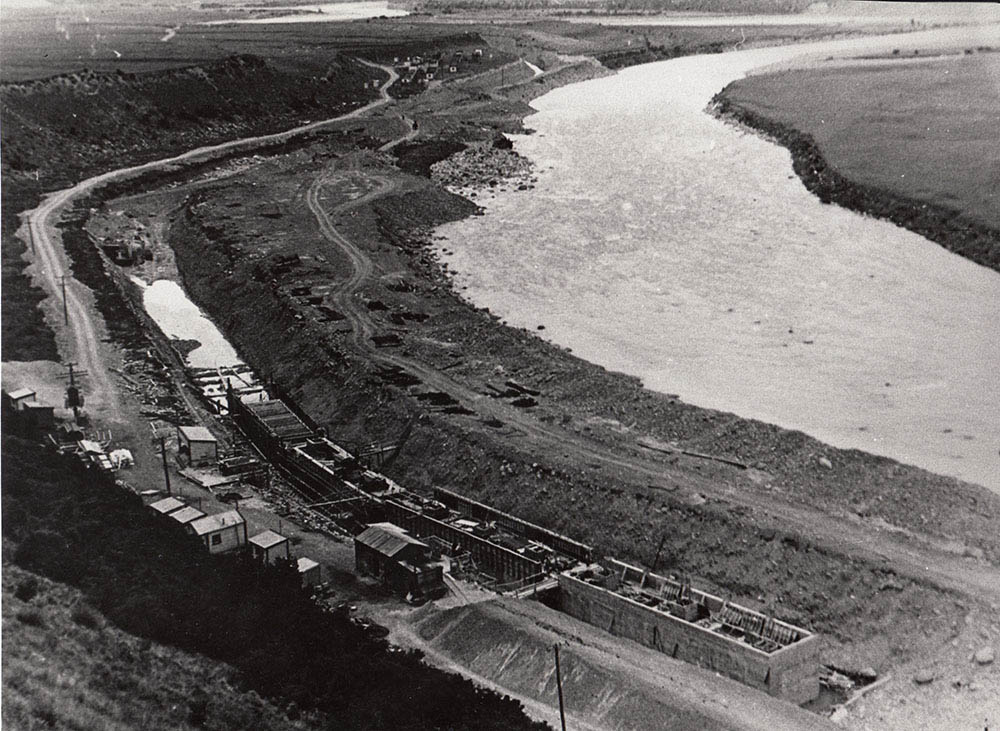

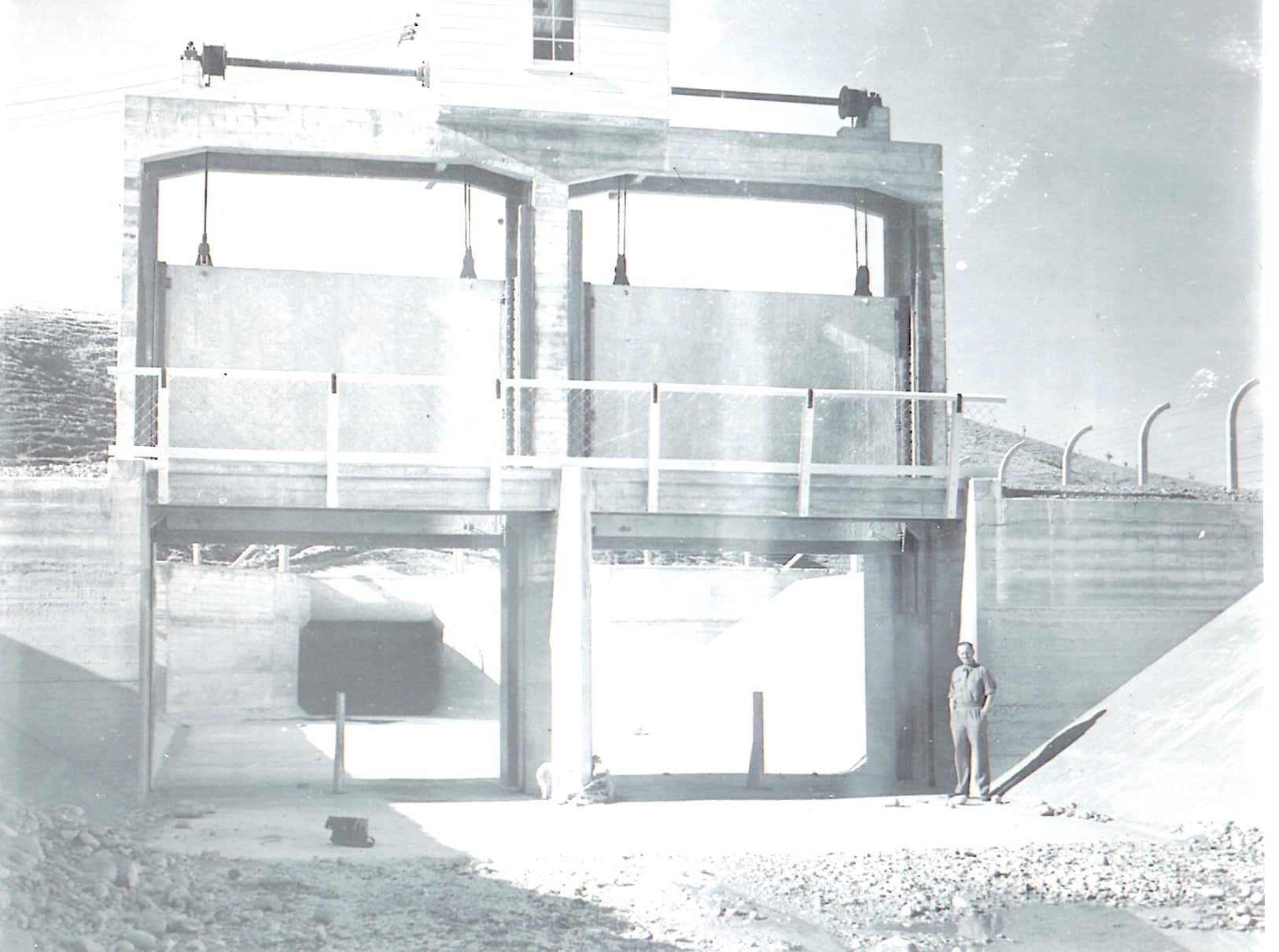

In the mean-time work on the huge 12-foot (3.7m) square caissons (intake structure) was underway downstream. Built in a line, one behind the other, they were then strengthened and reinforced by carpenters, ready to withstand even the largest of floods. Pump attendants worked around the clock to keep water out of the channel and away from the construction.

Klondyke – The Big Cut

When construction of the caissons (culvert) was nearing completion a major excavation task was looming – a project dubbed ‘The Big Cut’. This huge earthmoving operation required a channel to be excavated from the intake, around the men’s huts, to join up with the already completed race along the terraces further downstream.

Engineers had at their disposal two yard-and-a-half draglines, a 37RB Rushton Bucyrus and a steam dragline with a third (Bay City 65) brought over from Methven specifically for the job. Boulders larger than the bucket had to be brought out by developing techniques of working the drag chains under each side.

Upon completion of the channel the caissons were filled with compressed air at each end and floated into place above the intake. The channel was then filled back in to keep the river from flowing down into the partially excavated race below.

The caissons were sunk into the river and a control house was built on top of the intake structure. Central, radial gates were positioned between the upright piers with control wheels and drums connected to wire lifting ropes so the gates could be lifted to let in the water through the tunnel below.

Syphons

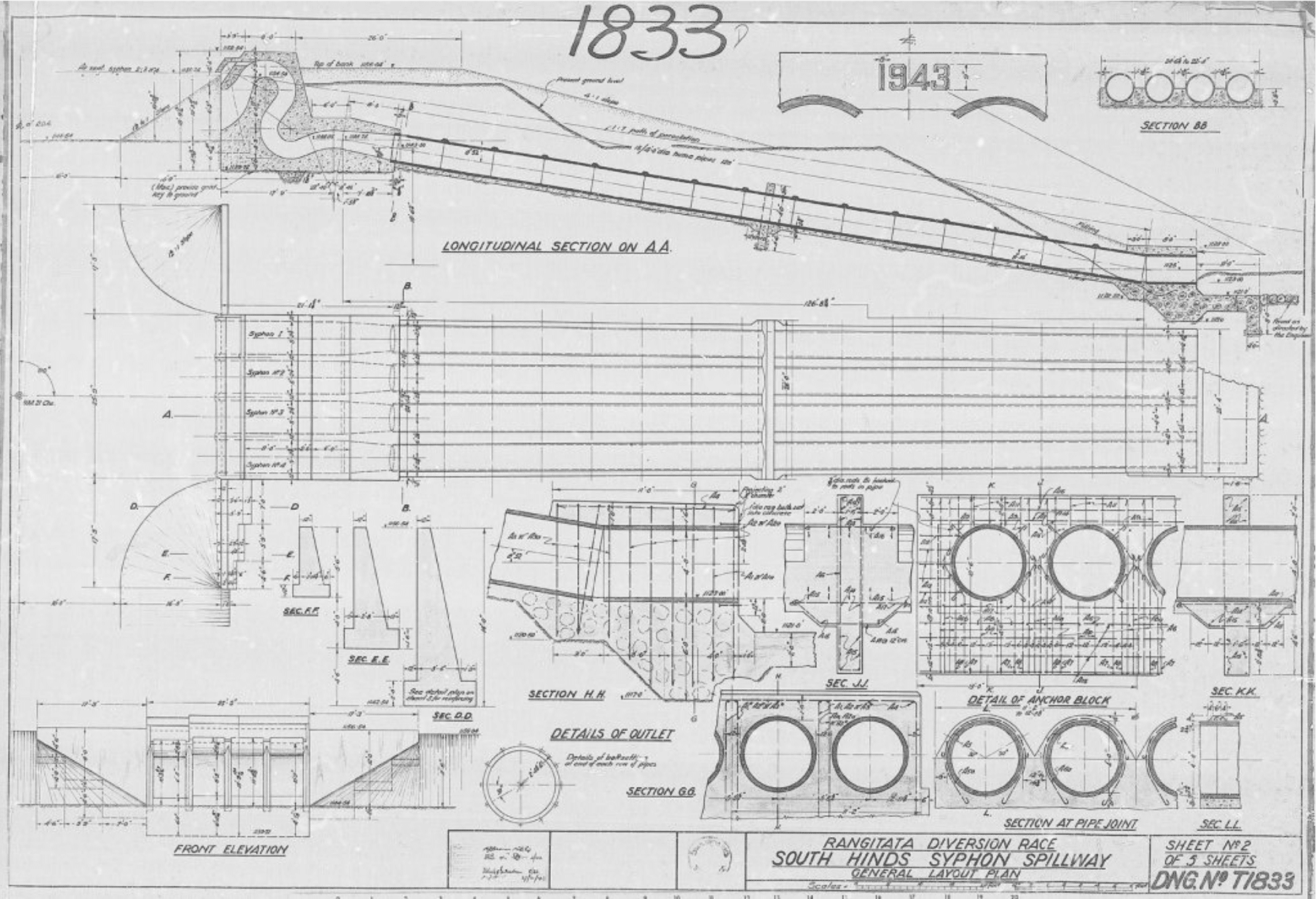

In all there are nine syphons along the length of the RDR. Starting from the Rangitata end they are: South Hinds, Surrey Hills, North Hinds, South Ashburton, Cave Stream, Bowyers Stream, Taylors Stream, North Ashburton and Dry Creek.

One of the most ingenious constructions along the race was the South Hinds automatic syphonic spillway, designed to save Anama and Mayfield from flooding. As one of the few automatic operations in the scheme at that time, it attracted a lot of interest. A lineup of four galvanised pipelines was inserted in the ground to channel water under a structure by the outlet to the South Hinds river.

One of the most troublesome constructions resulted in the Surrey Hills syphon being built. The unstable land provided high risk and sparked off the greatest engineering wizardry of the whole scheme.

Originally an open race was painstakingly carved around the boggy hillside. It was dangerous work on the slippery hillside and eventually had to be abandoned when a big slip happened over the Christmas break in 1938/39.

Undaunted, the engineer in charge, T.G. Beck is said to have called Public Works Minister Bob Semple and said the race would go on.

The pipe factory at The Birches Camp was commissioned to build “spectacular syphons big enough to take a car”. Three types of syphons were used, two were to by-pass rivers and the third to by-pass unstable country.

The syphons crossing North and South Ashburton Rivers were precast, reinforced pipes, 11 feet in diameter, nine inches thick and weighed 18 tonnes.

The Surrey Hills syphon, covering one and a half miles (2.7km), are one of the most outstanding engineering feats of the whole race because of their size and the high pressure they have to withstand, up to 123 feet (37m) of water at the deepest part.

They are 12 feet (3.65m) internal diameter, have a 10 inch (25cm) thick shell and weigh 28 tonnes. Anchor blocks, weighing 400 tonnes, are placed at strategic points at the base of the hills.

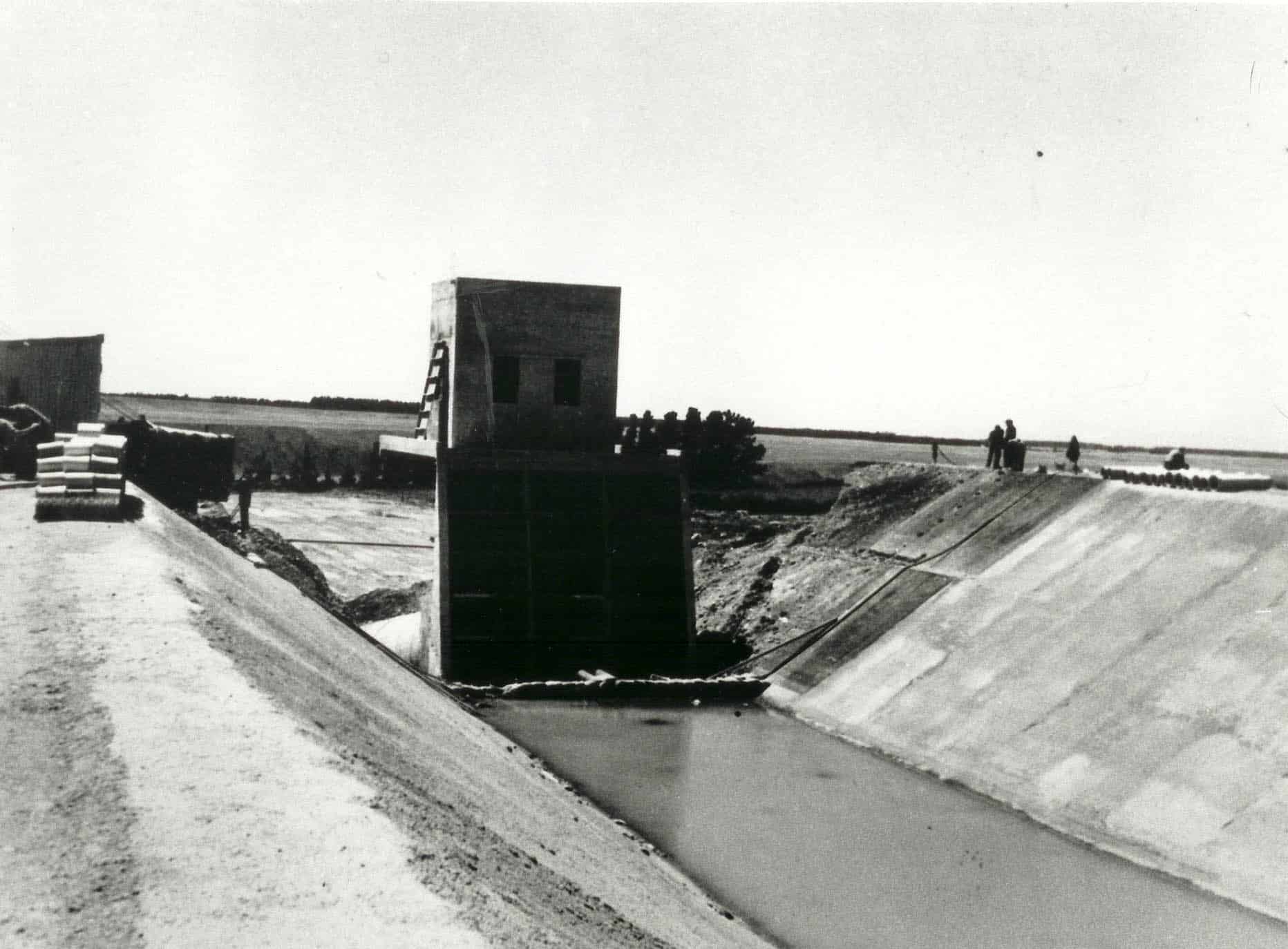

South Hinds syphon spillway

Race and Major Infrastructure

While work was progressing on the intake at Klondyke, excavation of the race continued on toward Montalto. Because the land dropped more than one foot per mile (190mm/km), three eight foot (2.4m) drops were originally constructed to take the fall and reduce scouring. These were removed in the 1980s when the Montalto Power Station was built.

The first road bridge across the race was built at Klondyke. Attention to detail was meticulous and things were built to last, which is very evident now, over 80 years on. Carpenters designed the moulds with chamfered edges, concrete shingle sourced from Orari was deemed to be the best in the country, and men who worked on the construction of the scheme had great pride in their involvement with such a prominent development. In total 61 bridges cross the RDR today.

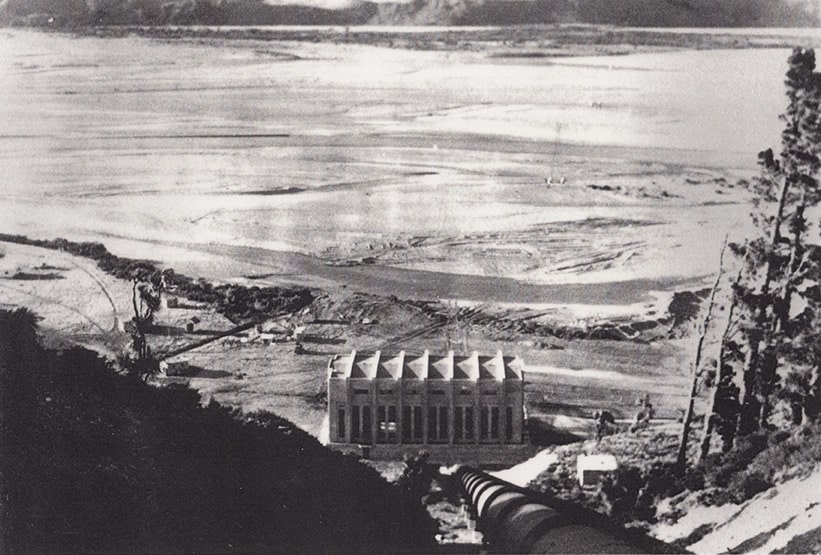

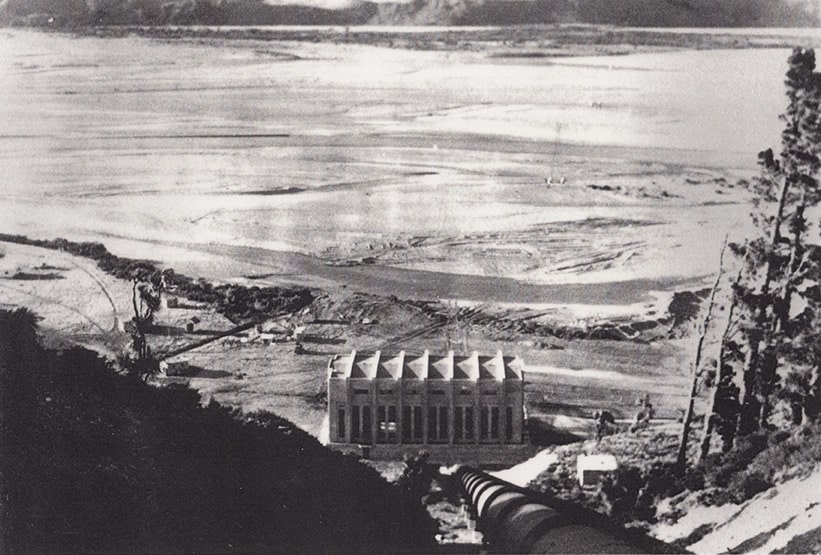

The Opening of Highbank Power Station

Located on the berm of the Rakaia River, Highbank operates continuously during winter, from May to September. When Mr Semple opened the Highbank Power Station in 1945 the crowds turned out to welcome him. Some had hoarded their war-time petrol rations to be sure of being there. Semple’s theory was that water that ran “to waste” was to be put to work. Energy that was normally dissipated in the riverbed was to be controlled in smooth running streams until it dropped quickly as a surging torrent to drive generators and create 36,000 horsepower (approx 25 megawatts).

Highbank Power Station opened in 1945

Engineering Recognition

Overview

Engineering New Zealand (formerly Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand – IPENZ) recognised the RDR as part of its “Engineering to 1990” project, which the Institution organised to help celebrate the country’s sesquicentenary in 1990. A plaque was unveiled to mark the significance of the RDR as part of New Zealand’s engineering heritage.

Engineering New Zealand engineering heritage record

Category: Engineering Work

Description: A 67.7 kilometre long race, begun in 1937, diverts water from the Rangitata River to irrigate 66,000 ha of farmland. This was New Zealand’s first major river diversion and largest irrigation scheme.

The concept was bold from the outset – a major diversion of a major river along the foothills of the Canterbury Plains for passing under major rivers on the way to discharge at Highbank, Rakaia River, using the power drop to produce 25.2 MW of electricity. The prime purpose of the race was to irrigate the farmlands of Ashburton County, raising production five or six-fold, and enabling maximum diversification of farming, be it cropping, meat and wool production, dairying, or fruit production. Although the irrigation was slow to get underway – taking some 20 years to reach full capacity, it has been a thorough success completely transforming the district.

The race is carried along the sidling of hills for many miles and unstable hillsides were encountered just south of the Ashburton River crossing. A 2.7km inverted syphon was substituted requiring twin pipes of such a diameter that the Minister of Public Works (the Hon R. Semple) drove a car through them. The pipes were made at a site near Mayfield and were believed to be the second largest spun reinforced concrete pipes made in the world up to that time.

In 1990, the ownership of the race was transferred by the Government to Rangitata Diversion Race Management Ltd.

Design: Public Works Department, T.G.G. Beck. [supported by F.R.Asklin, I.W.McKinnon, J.R.de Lambert, J.O. Riddell and E.E. Lawrence.]

2019 Display Board

In September 2019, RDRML unveiled a new information board about the history of the diversion race. Engineering New Zealand’s Canterbury Heritage Chapter collaborated with RDRML to resite the 1990 plaque in a more publicly accessible location, and it now takes pride of place by the information board.

What makes the RDR works worthy of Heritage Status?

The Canterbury Plains has natural features rarely found elsewhere – abundant alpine river water at high elevations, a landscape blessed with a gradient that makes water from the rivers transportable by gravity, in race or pipes, and soil with excellent drainage. A noted Israeli water engineer, Dr Sam Mandel, considered the Canterbury Plains the best location for irrigated agriculture in the world.

Realising the potential, however, required novel and innovative engineering design and construction. The 2.7km Surrey Hills reinforced spun concrete pipe was second only in size to the syphons in the Los Angeles Viaduct, all fabricated during the war years with little mechanical plant to assist. A remarkable effort.

Capturing and controlling diverted water here at the RDR intake from a steep braided river, was a problem never encountered in New Zealand on this scale. This led to a particularly New Zealand engineering solution – using mechanical plant (in this case a dragline and bulldozer) to “persuade” a part of the river flow to enter the intake. And then sensibly letting the river have its way during floods, before “persuasion” was again imposed.

Crossing major rivers at right angles with an open race has its challenges, especially when the rivers are flood prone and have rapidly changing beds. A largely unrecognised feature of the RDR has been the soundness of the design and operation of the 9 inverted syphons used for river crossings between the intake and Highbank Power Station.

It is also easy to forget that the design of the RDR system dates back to the 1930s, when the climatic and river flow data was relatively sparse in New Zealand. Modern day engineers have found that the assessments of irrigation water demand and estimates of power production made by the original design team, match well with those estimated using sophisticated computer models.

Along the way there are examples of stand-alone engineering features of interest – the syphonic spillway at the South Hinds River was a New Zealand first and has been operating successfully since its construction in 1943.

The changes that have been made since commissioning are equally impressive. The RDR deserves its heritage status, and were it better known, would warrant international recognition.